Soft Matter, Ant Trails, Breakdancing and Tensegrity

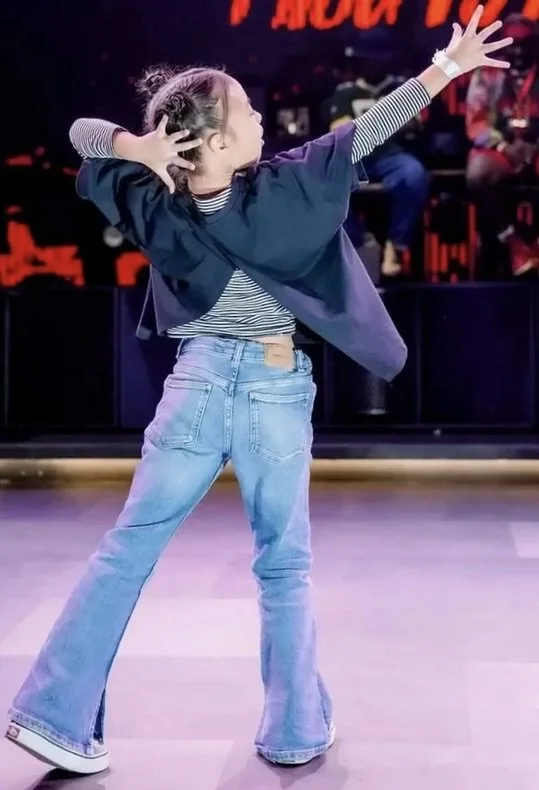

/Great video of miyu dancing is at end of post..

I was about to begin a much-needed mopping of the kitchen floor. For the past half hour I’d been procrastinating, engrossed in YouTube videos of Miyu Pranoto, an 11-year-old Indonesian breakdancer. My lifelong dream is that we are all dancers, each of us with the capacity to move expansively and effortlessly, fully occupying our bodies the way children do. But we’ve forgotten how that feels. For the past year I’ve been trying to develop a somatic practice that can help us remember. Miyu’s extraordinary performance got me thinking....

Tensegrity-informed Movement

As many readers know, I’ve been going on about tensegrity for some time. Tensegrity is a structural design principle that involves compressed components (such as struts or bars) that are suspended independently within a tensioned network (of cables or tendons) to form a structure whose stability and adaptability is maintained by the relationship between tension and compression. The tension network distributes load evenly through through the structure, making it both strong but also readily able to change shape. This contrasts with structures in which components are stacked like bricks, one on top of another, relying upon compression for stability, and lacking in resilience or adaptability to outside forces.

We usually describe human movement using conventional anatomy, but this doesn’t work if, as I suggest, our bodies are tensegrity designs rather than stacks of bricks. The belief that human movement is produced by muscle motors and bone levers is out of date. Living beings aren’t hard or solid matter; they’re soft, and soft matter operates according to different principles than do structures of steel, concrete or wood. Soft matter creations are adept at both tension and compression, so tensegrity seems a good premise from which to investigate both their structure and movement.

Anatomist and embryologist Jaap Van der Wal has said that human motion is a continual shaping and re-shaping of the body’s soft matter architecture. Miyu’s dance, in which certain shapes or gestures are accentuated by the beat of the music, seemed a clear example of such movement. It was also flowing, expansive, effortless, efficient, strong, omnidirectional, curving, unpredictable and complex—all qualities of soft matter in motion. No wonder I couldn’t tear my eyes away from this pint-sized phenom.

But I turned off my computer and considered my kitchen floor. What it would be like to pay attention to my own body’s shaping while I swept and mopped?

Complexity

There’s a bit more back story to this morning’s ruminations. My house is perched on an ant hill and, as my mother’s daughter, I fervently HATE ants.

Today’s trail from a forgotten cat food dish was no scouting patrol in single file. It was a battalion marching eight abreast. I followed the trail across the dining room where it turned a corner and streamed across my bedroom, under the bed and through another doorway into a far corner of the closet.

Coincidentally, I had just renewed my library loan of “Notes on Complexity “, by Neil Theise, a physician, scientist and prominent contributor to fascia research. Although this book is not about fascia, it pertains to the study of it. As mentioned earlier, the behavior of fascia can’t be understood by looking through the Newtonian lens that applies to hard things. The physics applicable to fascia describes it as complex: unpredictable, self-organizing and shape changing. Dr. Theise illustrates this aspect of Complexity Theory by describing the behavior of ant colonies.

A random ant in search of food leaves hormone footprints along the way which entices other ants to follow the trail, each one depositing more hormones and attracting more and more ants so that eventually an army emerges from your closet. Ants have no leader and yet their assault can ruin your plan for the morning as surely as if their president has been shouting orders from a rooftop, or up through the pipes in the basement. The ants’ movement was, like Miyu’s, flowing, expansive, effortless, efficient, strong, omnidirectional, and unpredictable. The word “inexorable” also came to mind, a perspective tinged by my ant aversion.

It was time to get out my mop and broom.

The Shapes of Walking

But I sat mesmerized by this small girl. Her movement was too fast for me to track the kaleidoscopic shapes that flowed between the ones emphasized by rhythm or expression. I tried slowing the video by advancing it with an arrow key. But I got nowhere because, in fact, she wasn’t making the shapes. The shapes were moving through her fascial body. This was not magic: self-assembly is another of soft matter’s mysterious properties.

I don’t know whether Van der Wal’s characterization of movement as shaping is correct, but I find it a useful way to begin thinking holistically about my own body’s movement. For example, take walking:

In order to walk, my intention to go somewhere sets off a slight forward inclination of my torso. Then, as I’m being impelled onward by gravity and momentum, a foot swings forward of my body, both to prevent me from falling and to prolong forward motion. That’s called “taking a step”. Ordinarily it’s regarded as a muscles and bones procedure.

But we now know that fascia is not inert tissue. It stores and transmits energy, including the forces acquired through its encounters with gravity and momentum. This offers an alternative way to experience walking: my fascial body as a whole negotiates my changing relationship with gravity and momentum via infinitesimal and instantaneous changes in shape. Muscles and bones assist the process by quickening or slowing the flow of shapes as needed—for example, when trekking across a field of gopher holes. Fascia is the main performer, with muscles and bones playing supporting roles.

How might walking feel if I forgot about taking steps, or pushing off, or swinging my arms, and simply opened my body to receive a flow of shapes?

Sitting with it...

Beginning to conceive of and to experience our bodies as wholes can be disorienting, because the bits-and-pieces perspective of the body is deeply ingrained. We’ve been taught that our bones, muscles, organs, the tubes of circulation and the wires of neural communication are all contained within a ubiquitous connective tissue referred to as fascia. Images in anatomy books confirm this reductive view. This is not our fault— the daring Renaissance fellows who curiously cut into bodies deserved to investigate whatever they found most interesting. So, assuming that connective tissue was mere wrapping, they tossed it in a bucket and built their conception of the body as a machine out of the interesting parts they had discovered. Although this idea has been beneficial to humanity for several hundred years, it was but a baby step toward understanding the body.

Twenty-first century fascia anatomists take us in a different direction. Fascia is regarded by many of them as the body’s constitutive substance. The organs necessary for life—muscles, viscera— everything—evolve from the fascial matrix (because soft matter is self-assembling) and are embedded within it. Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that fascia has a communication capacity that is broader and faster than that of the nervous system. Thus, we are whole beings from the beginning—sentient whole beings—the inverse of what we’ve assumed for four hundred years, that our wholeness is constructed from parts.

Tensegral Expansion

I roused myself and gathered my supplies. Viewing the floor-cleaning project as somatic research rather than a chore made it somewhat more appealing.

This was not my first experiment with tensegrity-informed movement, so I knew that finding the defining balance of tension and compression would require establishing a basis of comfortable expansion within my body. Such spaciousness would give me stability as well as the capacity to readily change shape. But because this was soft tissue expansion, subject to the Complexity rules of soft matter, how I achieved it could seem paradoxical.

First, the expansion needed a hint of resistance, something like being an open umbrella, but it shouldn’t require effort. For an umbrella, openness is its natural state, so being open doesn’t produce tension in the ordinary sense of that word. But the fabric of the umbrella does have tension in it. Tone is a better word for the sensation I was looking for. I wanted to feel toned or tuned the way a guitar string is tuned.

Second, comfortable expansion requires resilience. I didn’t want to be puffed up and stiffened into a position. To be comfortable, my expansion needed some “give” in it so my body could glide from one shape to another.*

For Miyu this way of moving seems inborn, perhaps stemming from generations of Indonesian dancers. But I was attempting to remember or re-create my own shaping. At first I’d have to perform my cleaning dance in super slow-motion. I would need time to focus on maintaining a spacious interior volume while the outer shape of my body bent and straightened and twisted and pushed. Especially challenging was squeezing myself into the far corner of the closet. But I found that by staying present with my sensations, I could remain spacious inside while accordioned on the outside.

Perception of comfortable expansion was fleeting, so I had to renew it again and again until it became familiar. When I got it right, there would be a moment when I seemed to occupy the full dimension of myself, despite doing a chore I didn’t want to be doing. I could imagine the air, tangible, brushing against every skin surface as my body shaped and re-shaped. Inside there was a humming sensation as if a chorus of cells and tissues rejoiced in the work they were doing together.

But maintaining focus on slow-motion mopping was hard work. After about twenty minutes, when my concentration frayed, I stopped and left the job half-done. That I could do that without inner skirmish was amazing. My habit would have been to rush and get it over with, a sure way to put creases in my hard-won spaciousness

Another amazing thing was that after a short rest, I found that movement felt easy and strong for several hours without my having to attend to it. That mere half hour’s focus on my body’s tensegrity had made an impression.

Moreover, I had forgotten that ants were my enemies. Perhaps prioritizing space within my body gave me distance from the ancestral ant-hatred. My newfound respect for ants as complex and self-organizing creatures likely contributed as well.

For sure, tensegrity practice seems one worth pursuing—my own baby steps toward remembering wholeness.

*I believe I’ve stumbled upon a somatic algorithm that can help establish the tensegral expansion described above. As soon as I feel confident about the best way to teach it, I’ll share with everyone. Stay tuned.

© 2025 Mary Bond

Thanks for reading, and for sharing.